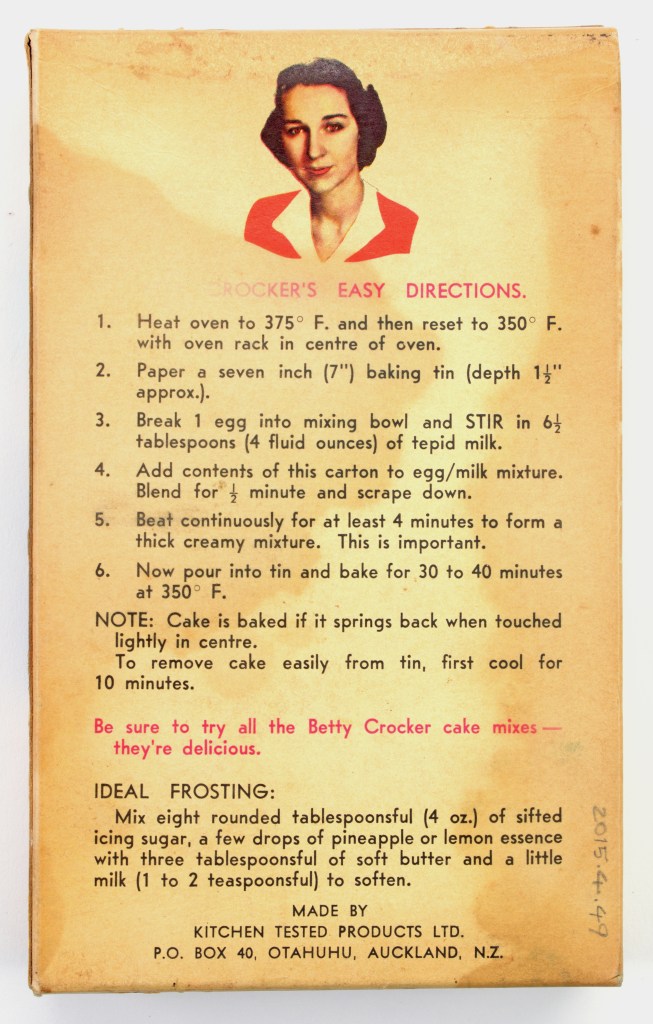

Since Betty Crocker became a household name in the 1940s and 1950s, millions of devoted fans have made the pilgrimage to the Betty Crocker Test Kitchens, each hoping the learn some of the secrets of America's First Lady of Food—and, maybe, even catch a glimpse of the woman herself.

Before the kitchen closed to visitors in 1985, tour guides would often find themselves in an uncomfortable position, faced with comforting shocked guests brought to tears when they learned that the treasured American icon never existed.

Betty Crocker

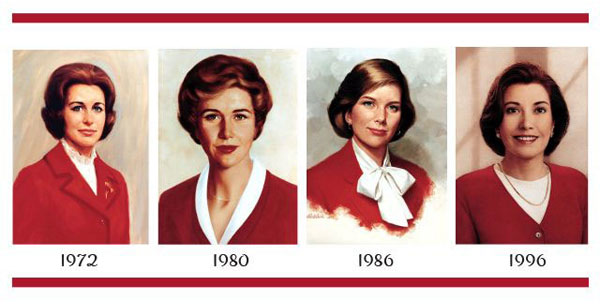

To these visitors and millions of others like them, Betty Crocker embodied their ultimate guide and teacher, a comfortable and knowledgable figure to turn to when no one else could help. For the last hundred years, Crocker has allayed women's fears decade after decade, metamorphosing throughout the twentieth century to embody that particular moment's cultural ideal and assist homemakers aspiring to the same.

The History of Betty Crocker

Betty Crocker was born in 1921, an accident of a rogue advertising campaign. That year, the Washburn-Crosby Company ran an ad for Gold Medal Flour in the Saturday Evening Post featuring a jigsaw puzzle that readers could assemble and return for a prize. Thirty-thousand completed puzzles surged into the offices, in addition to something curious the executives hadn't anticipated: countless letters seeking personalized cooking advice.

In the 1920s, American women were facing a distinctly new obstacle: the electric kitchen. In post-war America, the burden of kitchen labor was rapidly changing from shared responsibilities—either between extended family or hired help, depending on social status—to the job of a single person, the housewife. The Washburn-Crosby Company, a flour milling company that would later become General Mills, Inc, quickly surmised that these newly anointed homemakers greatly needed a mentor to assist them with both their new appliances and new role as homemakers.

In response to these new technologies, a new scientific field rose in tandem, that of home economics. While Washburn-Crosby's small, male-dominated marketing department sought to respond to the anxieties of home cooks, initially responding to each letter individually, they relied on the expertise of the company's female home economists in this correspondence. But as the volume of mail increased, executives realized the need for a true cooking authority, a woman who understood the concerns and frustrations of these women. And so Betty Crocker was created and dubbed the company's Chief of Correspondence.

The company immediately sought to make the character both distinctive and personable. While executives chose the last name "Crocker" as it was the name of Washburn-Crosby's recently retired director, William G. Crocker, the company thought "Betty" was a name American women would find simple and familiar. Female employees company-wide submitted Betty Crocker signatures before one, penned by secretary Florence Lindeberg, was chosen for its distinctiveness. Soon, Crocker was receiving so much mail that other employees had to be trained to reproduce its contours.

The Many Faces of Betty Crocker

While Betty Crocker was not a real person, she was brought to life by one. Marjorie Child Husted joined Washburn-Crosby as a cooking instructor in 1924, just as Crocker found her voice in a company-sponsored radio show titled the "Betty Crocker Cooking School of the Air," which first aired on Minneapolis radio station WCCO before going nationwide. Husted quickly took over the company's Home Service Department, encouraging her test kitchen to create foolproof recipes that even novice home cooks could make with ease and style.

A champion of the science of home economics, Husted committed herself to making Betty Crocker both aspirational and authoritative. Husted herself wrote all the scripts for the radio cooking show, recorded her own voice as Crocker, and created numerous quirky segments, including "The Betty Crocker Magazine of the Air."

Betty Crocker

With Husted's help, Crocker fully penetrated the American consciousness through the airwaves, especially during World War II when the War Food Administration commissioned a radio series from General Mills entitled "Our Nation's Rations." During this time, according to culinary historian Laura Shapiro, Crocker "became a coast-to-coast personification of patriotic home cooking." By 1945, Betty Crocker was receiving more than 4,000 letters a day. That same year, Fortune deemed her the First Lady of Food and named her the second most popular woman in America, second only to Eleanor Roosevelt.

As Husted would later recall,

Women needed a champion. Here were millions of them staying at home alone, doing a job with children, cooking, cleaning on minimal budgets—the whole depressing mess of it. They needed someone to remind them they had value.

While Husted was the first to embody Crocker, she was far from the last. In 1949, only two years after full-scale television broadcasting began in the United States, Washburn-Crosby hired actress Adelaide Hawley to portray Betty Crocker on radio and television. (Although she embodied the fictional authority for fifteen years, Hawley herself never enjoyed cooking.) General Mills dropped Hawley as spokeswoman in 1964, seeking a more sophisticated image as women made political advancements in the 1960s.

Ever a marketing tool, Crocker's image, and tone have continued to morph to meet the needs of American women throughout the last fifty years. As Betty Crocker celebrates her hundredth birthday this year, her image looks more youthful than ever before.

Happy Birthday, Betty

Today, perhaps you don't think of the woman herself when you hear Betty Crocker's name. Perhaps, instead, you simply think of the signature on Betty Crocker products, a smooth, branded logo rather than a distinctive scrawl atop your cake mix or brownies.

Although executives hand-picked Betty Crocker's signature in the 1920s for its singularity, the trademarked cursive autograph that appears on General Mills' red spoon logo today is a far cry from the original. Just as with her portrait and the narrative she embodies, Crocker's signature has repeatedly been smoothed and transformed over the last century.

Throughout the last century, advertisers and executives have sculpted and re-sculpted her image to fit the ever-changing idealized image of a woman who could answer all of America's questions. And it's worked. To this day, Betty's distinctive red spoon remains a beacon of accessible domesticity, 100 years later.