In its simplest terms, fatphobia is the word used to describe when people discriminate against people with bigger bodies. For some, this is rooted in a fear of becoming overweight or obese, and for others, it's the result of the beauty ideals our society has thrust upon us—especially for women.

But thin bodies haven't always been the most appealing. The evolution of the ideal body type in today's society wasn't by accident, according to many historians and academics. It was cruel, calculated, and largely the result of racism.

Evolution of the Ideal Body Type

To understand how racism fuels today's ideal body type, you have to take a walk through history. In ancient civilizations, full-figured women were the ideal body type. Society associated their curves with sensuality, fertility, status, and beauty.

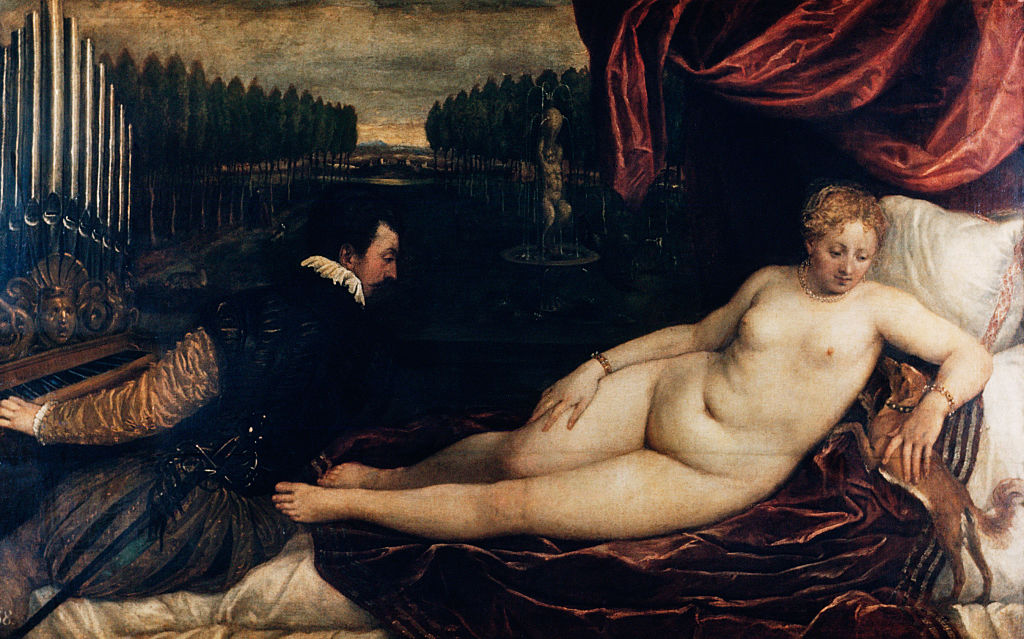

(Photo by Francis G. Mayer/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images)

Artists captured these ideals in their work throughout each era. In 1550, Titian painted Venus with an Organist and a Dog featuring a full-figured Venus lying across a blanket, adorned with golden jewelry. The organist gazes at her body with intrigue, while her posture exudes sensuality and confidence. This was the ideal body type in Italy and much of Europe at the time.

A woman's weight signified her status during this era, as they were well nourished and didn't want for food or other necessities. In 1635, this remained the ideal with Peter Paul Rubens' The Three Graces, which depicted nude goddesses. Goddesses embodied the highest level of beauty, which included rounded hips, thick thighs, and curvy tummies.

(Photo by Carlos Alvarez/Getty Images)

This ideal for beauty didn't last much longer. Once the first slaves reached the Americas in 1619, beauty ideals began to shift. Dr. Sabrina Strings is an expert on this topic, having studied it for many years. Her research highlights how beauty standards shifted to justify and perpetuate slavery in the Americas.

Slavery and Beauty Ideals

European settlers in the Americas originally justified slavery through skin tone alone. However, as slave masters fathered children with their slaves, skin tones became less binary and more variable. As a result, they added more supposed characteristics that made slaves inferior to white women of status, according to Dr. Strings.

In addition to skin tone, American society decided that slaves lacked self-control, making them gluttonous and promiscuous. Their overindulgence in food made their bodies larger and curvier than white women. So, these falsehoods caused white Americans to cling to beauty ideals that valued smaller bodies with fewer curves.

These ideas led to a centuries-long rejection of fat people that disproportionately affected Black women and girls.

Healthcare and Body Shaming

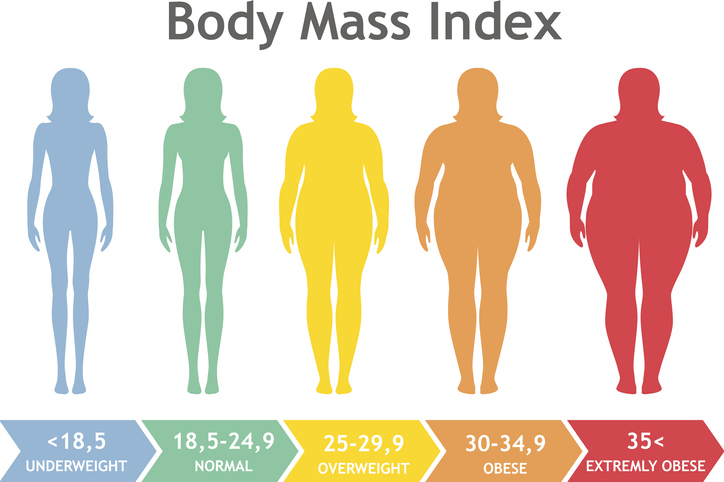

Racist ideals for body types have followed American society well into the 21st century. Standards for health and body composition took hold with the introduction of body mass index (BMI) in 1832.

Once doctors started using BMI as a measure for a healthy weight, things only got worse. This development gave a scientific basis for racist ideas about weight and body size. Since BMI is calculated using height and weight alone, it lacks consideration for body composition including muscles, bones, and cultural and genetic influences.

Getty Images

As a result, Black people are often labeled as obese, and the healthcare system attributes the disparities they experience to their weight. However, Black Americans only have a 7.4% higher rate of obesity than white Americans. So, the existing healthcare disparities that cause Black women to die three times more often during pregnancy and childbirth, twice as many deaths among Black men diagnosed with prostate cancer, and make Black people two times more likely to die from heart disease than their white counterparts can't result from these weight differences alone. Rather, there are only correlations between weight and health outcomes, which do not have a causal relationship.

These wide disparities don't add up with the slight differences in the rate of obesity between these two populations. The only explanation is that racism and fatphobia prevent Black people from receiving quality care from healthcare providers. And the disparities have only become more clear during the pandemic as Black people are dying at a higher rate than white people from COVID-19.

Fatphobia's lasting effects

The toll that fatphobia has had on society is significant. It led to the uprising of diet culture and eating disorders, the cost of which has had rippling effects for Black women and girls. It's caused self-esteem issues that have only worsened with the advent of social media.

Fat-shaming Black people for having curvier bodies needs to end. As a society, we're headed in that direction with the current body positivity movement, but that isn't enough.

We need to dismantle the systemic racism and anti-fat attitudes that allow doctors to deliver subpar healthcare to Black people in particular. Encouraging weight loss can be productive if that is a patient's goal, but they shouldn't be chastised for the excess weight they carry.

The bottom line is that thin bodies are not a sign of good health, nor are fat bodies indicative of poor health. Fat people and thin people both deserve quality medical care irrespective of their weight and skin tone, and our healthcare system needs to make it happen.

Brianna Graham, MPH, CPH, is the Founder and CEO of Mixed Media, LLC, a black-woman-owned consulting business. She has a Bachelor of Science in Health Administration from George Mason University, and a Master of Public Health from The University of South Florida. Currently, Brianna holds a certification in public health, and a teaching certificate. She is an expert in consulting, writing and editing for healthcare and education organizations.