Before Duncan Hines was associated to cake mixes, the son of a Confederate soldier pioneered restaurant ratings in Bowling Green, Kentucky.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the world was opening for Americans. Railroads had quickly become commonplace, replacing rigorous overland travel with affluent tourism. Rumors spread about the advent of motor cars as industrialists raced to bring automobiles into mass production. Americans began to move around the country at speeds and in numbers never before seen, and businesses sprang up to greet them—barbecue stands, diners, and ice cream parlors.

The problem? Restaurant kitchens' cleanliness... or lack thereof.

Duncan Hines gave sound advice on the matter: "Go into a restaurant and first, demand to see the kitchen and inspect it. Then eat in the restaurant. If they won't let you into the kitchen, just leave."

Such posturing seems inconceivable in an era of strict health codes and rigorous inspections. But with the formation of the Food and Drug Administration still thirty years away, eating at an unknown restaurant could have serious health implications if you chose incorrectly.

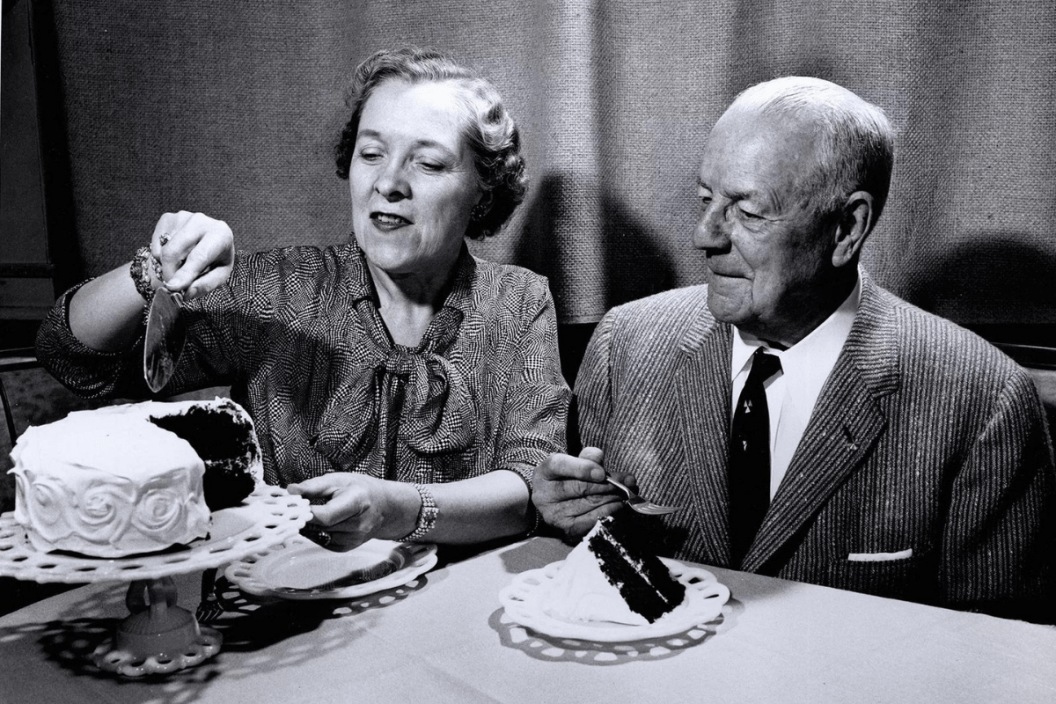

Like Betty Crocker, Duncan Hines was much more than a spokesperson paid to sell baking mixes—and, unlike Crocker, he was a real person. Long before Hines was a face on a box of cake mix, he was a traveling salesman taking rigorous notes on the restaurants he encountered on the road. Those notes would become the roadmap for American restaurant criticism as the century unfolded.

An Unlikely Food Critic

Born in Bowling Green, Kentucky in 1880, Duncan Hines was one of six children and son to a Confederate captain. After his mother died when he was only four years old, Hines and one of his brothers were sent to live with their maternal grandmother, as his father found raising six children alone was too much to bear. His grandmother's cooking first instilled in him an understanding and care for food, although he never learned how to cook himself.

WKU Special Collection

After attending the Bowling Green Business School, Hines married Florence Chaffin and the pair moved to Chicago. There he joined an advertising firm that required travel across the country. His wife would often join him on these cross-country sojourns, and they quickly began to explore on the weekends, too. According to some estimates, from the early 1920s into the 1930s, the pair would traverse up to 60,000 miles a year together.

During these trips, Hines began to keep a personal journal of the places he'd enjoyed eating at, keeping a record of their addresses, hours, and his favorite dishes. He often shared these travel tips with friends and coworkers, who would share them in turn. Word spread of his notations, and by the early 1930s, Hines was receiving an onslaught of calls and letters asking for advice. Hoping to quell some of this activity, he compiled a list of 167 restaurants—throughout thirty states—and sent out the booklet alongside the family Christmas card. This had the opposite of the intended effect, and the queries continued to mount.

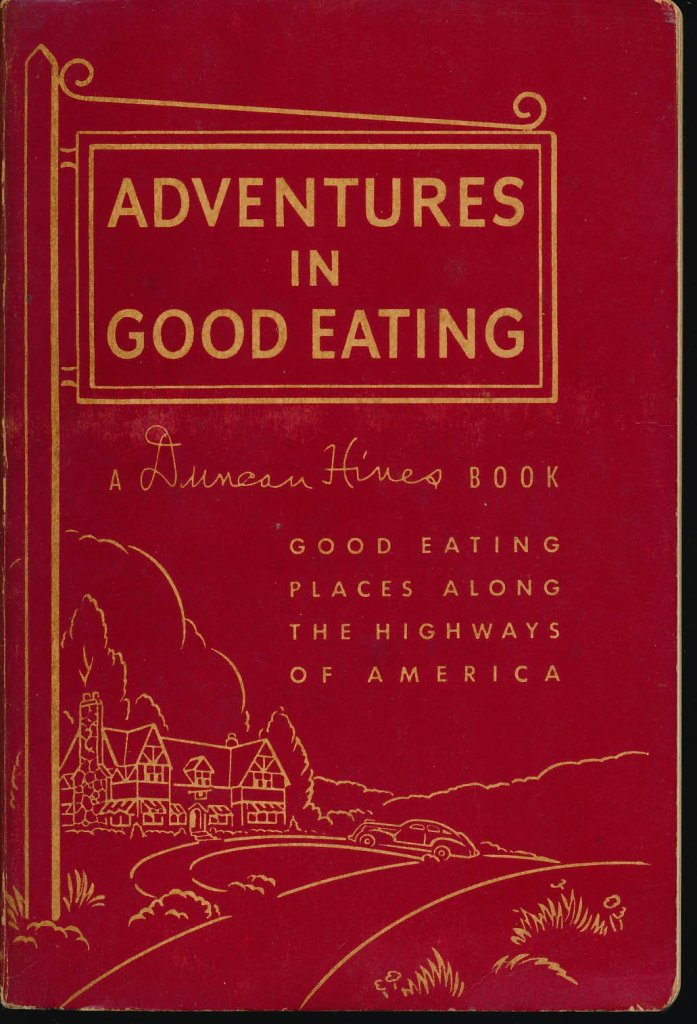

By 1937, Hines self-published his first guide to travel food, Adventures in Good Eating, at fifty-five years old. He sold them for one dollar each.

A Book in Every Glovebox

At the time, comparable guides existed, but they were purely pay-to-play, with paid reviews functioning as advertisements. Although Hines would accept gifts from restaurants after publication—once even receiving a Cadillac—he took great pride in his initial impartiality. Hines made reservations under fake names and printed an old photo of himself alongside his writer's bio so that restauranteurs would not be able to recognize him on the road.

But rather than providing true gastronomic guidance, Hines' guides were far more about assessing and enforcing both health standards and social codes. (He stressed that innkeepers should not allow drinking and should only accept guests who arrive with luggage, for example.) These lists were tailored to white travelers with financial access to motor excursions. Often, the biases of white sightseers were on display—As one writer notes, "his review of a now-defunct Japanese restaurant in New York City includes mockery of the waiter's non-native accent."

But as leisure travel boomed in certain parts of the American public, the hunger for these guides became insatiable. Hines quickly published more guides, including Lodging for a Night and Adventures in Good Cooking, which also sold en masse. As the government built new highways systems and road travel continued to flourish, Hines' guides could be found in glove boxes across the country.

To meet the constantly changing American landscape, the books were continuously updated and reprinted annually. Soon, signs reading "Recommended by Duncan Hines" began appearing in restaurant and hotel windows, a precursor to the similar, modern Zagat and AAA recommendations.

A Salesman Once More

In 1945, a New York businessman saw even more potential in the Duncan Hines brand, by now a household name. The two partnered and Hines licensed his own image to appear on myriad products, understanding the cultural weight of his own seal of approval. By 1950, the Hines-Park Company was selling more than 250 canned and boxed products. His cake mix appeared the next year, and by 1952 became the most popular of those products, cementing his legacy both on and off the road.

Although Duncan Hines was the godfather of American restaurant criticism, he was far from an epicure. Late in life marketing campaigns would show him in chef's whites, but in truth, he never learned how to cook. Even his palate was questionable: Hines once bragged that his ideal cocktail was an unholy concoction of gin, grenadine, egg, honey, and pickled watermelon juice.

As he writes in an introduction to his first book, Adventures in Good Eating, "There is no accounting for tastes in food any more than there is in clothing, printing, or marriage."

Products featured on Wide Open Eats are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our links, we may earn a commission.

Katie King is a writer, researcher, and producer committed to exploring the overlapping intricacies of American history, culture, and foodways. A Georgia native, she currently resides in San Francisco with her husband and four bouncing rescue animals.