Visit any major city (and most of the small ones, too) and you'll find food trucks. These mobile kitchens move from day to day, setting up in one spot to prepare and serve food. At lunch time, you'll find crowds of office workers gathered around them, sitting on the grass or steps nearby to eat their wraps and fish tacos and pizza slices. But food trucks aren't really a new invention. They have a long history, including a founding role in the exploration of the American West. Chuck wagons were the first food trucks, using cowboy cooking to bring food to workers on the move.

National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum

This style of frontier cooking, or cowboy cooking, can be found throughout stories of the Old West, from Little House on the Prairie to Lonesome Dove. From wagon trains headed to California to the cattle drives moving herds of beef north from Texas, hearty food was cooked over an open fire and eaten wherever one could find a comfortable spot on the ground.

Self-reliance, ingenuity, and practicality are considered hallmarks of cowboy cooking and while they have never truly gone away, more people are seeking ways to emphasize those ideas in their cooking today. So grab a seat around the fire, say hello to Cookie, and let's talk about chuck wagons and cowboy cooking.

History of the Chuck Wagon

While the style and tools of cowboy cooking were used throughout the exploration of the American frontier, the actual chuck wagon era only covered about 20 years.

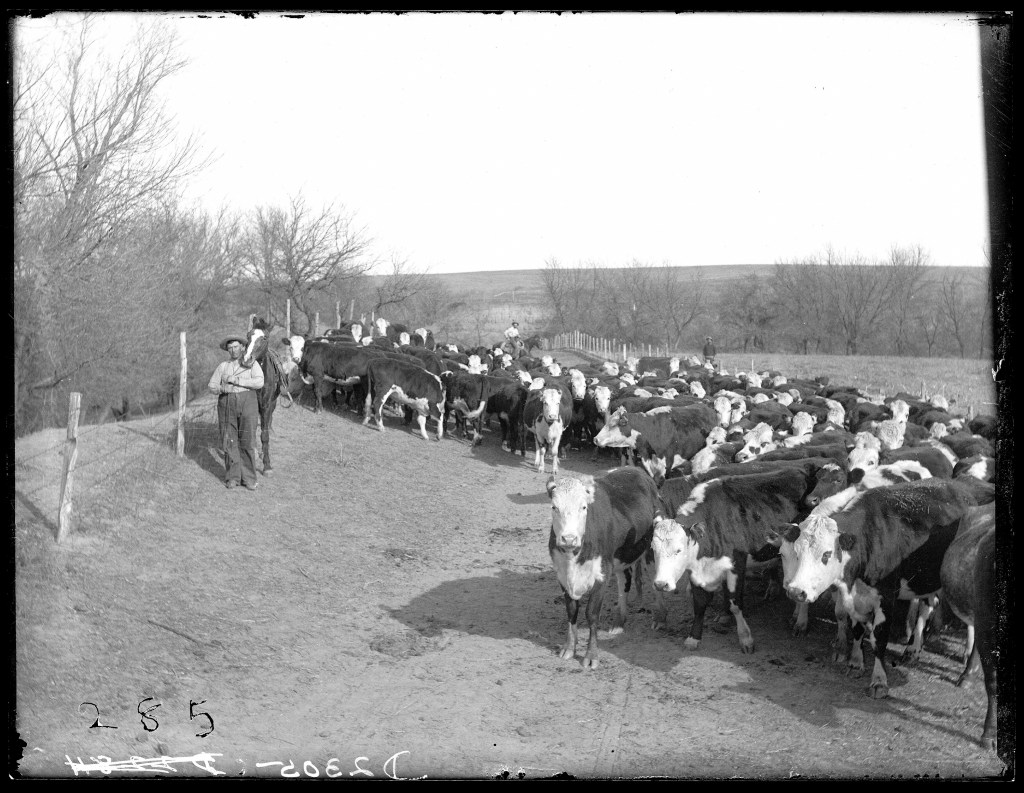

After the American Civil War, a man named Philip Danforth Armour opened a meat packing plant in Chicago, Illinois (and founded meat-packing giant Armour and Company). Getting the large number of cattle required to fill the plant's orders required shipping them in via Western railroads. Getting the cattle to the railroad involved a long, arduous cattle drive from the ranches in Texas mostly to the railhead in Abilene, Kansas, or other Kansas towns like Dodge City or Wichita or Ogallala, Nebraska.

Library of Congress

The drives lasted anywhere from a few weeks up to five months and covered 12-15 miles a day on average. It was hard, dusty, intense work, but with the sheer number of cattle being transported, the need for cowboys was great.

In 1866, Texas rancher Charles Goodnight came up with an idea to make his outfit more attractive to prospective cowboys: feed them better with a mobile kitchen.

Up to that point, cowboys pretty much ate whatever they could carry with them, which was mostly dried beef and hard biscuits. Goodnight changed all that by centralizing food storage and cooking.

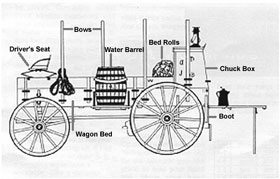

He took a surplus Army wagon made by Studebaker and turned it into a mobile kitchen. A box with a hinged door was bolted to the back of the wagon; outfitted with shelves and drawers, the box both carried supplies and turned into a flat work surface.

Beneath the box was a "boot" which carried larger and heavier items, like the ubiquitous cast iron dutch oven. A water barrel and coffee grinder was attached to the outside of the wagon. A "possum belly" was suspended beneath the wagon; this stretched canvas or cowhide carried fuel for the campfire, usually wood or cow chips picked up along the trail.

There are two stories about how the wagon came to be known as a "chuck wagon." The first is that it was called so because "chuck" was slang for food and the box bolted on the back of the wagon was a chuck box. The second is that the wagon was named for its creator, "Chuck" Goodnight.

Either way, Goodnight was without a doubt an innovator and soon trail crews everywhere had adopted the chuck wagon to provide tasty food for their cowboys. Today the chuck wagon is honored as the official vehicle of Texas.

Cowboy Cooking on the Trail

Library of Congress

In all the stories of trail drives and chuck wagons, the chuck wagon cook is almost always a gruff, surly man with an iron ladle and the respect of all the cowboys. The reality is probably not that far off the storied mark.

The cattle drive cook, or Cookie as he was often known, worked longer hours than the rest of the crew. He was responsible for setting up and breaking down camp, including starting a cook fire at each site, having dinner ready when the rest of the trail crew arrived, and getting up before everyone else to prepare coffee and breakfast.

Next to the trail boss, the cook was the most important person on the crew (and also one of the best paid crew members). He was also the barber, banker, doctor, dentist, and letter writer, as well as camp counselor and referee, settling issues among the rest of the crew. No one crossed the cook on a trail crew if they wanted to eat well.

Chuck wagon cooking was simple. Food on the trail was whatever was easily preserved and carried on the wagon: salted meats, onions, potatoes, flour for biscuits, and, yes, beans (although beans weren't as common as movies tell us, because of their long cooking time). Beef was, of course, readily available, and trail cooks were adept at using beef in numerous ways, including fried steaks and stews.

A specific etiquette grew up around trail cooking. No one ate until Cookie called (there was no sneaking little bites before the meal was ready). You did not ride up wind of the wagon, in order to keep dust from getting in the food. No one took the last serving unless they were sure they were the last man. And if you were refilling your coffee cup and someone yelled "Man at the pot!" you were obliged to refill everyone's cup.

Cowboy Cooking Today

What we think of as chuck wagon or cowboy cooking was common across the American frontier. While the chuck wagon was a product of the Texas cattle drives, the food itself was similar to what pioneers cooked as they moved across the West, all the way to the Pacific.

It's that style of American cooking that is seeing a resurgence today as people look for authenticity, plus a chance to slow down and do things by hand.

In 1997, a group of Old West enthusiasts and wagon masters created the American Chuck Wagon Association with a mission of preserving and presenting the heritage of the chuck wagon. The association has members in 31 states, Canada, Germany, and France who participate in cook off competitions, cooking demonstrations, charity events, and school visits, as well as offer chuck wagon catering.

Events are centered around setting up a camp, showing off restored or replicated chuck wagons, and cooking, of course. Participants use authentic cooking equipment from the era to showcase cowboy cooking techniques and recipes, involving outdoor cooking and simple ingredients.

You can find future events and winners of past events listed on the ACWA website.

And if you're interested in learning how to cowboy cook over an open fire, there are several opportunities across the West. Every spring and fall, Kent Rollins hosts a Chuck Wagon Cooking School in southwestern Oklahoma or northern Texas.

Or you can check out A Taste of Cowboy, the cookbook that Kent and his wife Shannon released in 2015 to make cowboy cookin' available to anyone.

Recipes for the Range or the Home

Dutch oven cooking is in many ways synonymous with cowboy cooking. The dutch oven could be used on the trail for main dishes, breads, and desserts. While you don't need an open fire for the recipes below, a good piece of cast-iron cookware helps.

1. Son of a Gun* Stew

Also known by another, slightly more coarse, name when it was just cowboys around. Stew was a common meal on the trail since beef was available and potatoes and onions could easily be carried on the chuck wagon.

2. Campfire Buttermilk Biscuits

Because nobody does dutch oven cooking better than Lodge Cast Iron cookware, this biscuit recipe is easy, versatile, and feeds a crowd (or a few hungry cowboys).

3. Cheesy Refried Bean Casserole

We can't talk about frontier cooking without a recipe from the Pioneer Woman. This cast iron skillet casserole is perfect for an open camp fire or for a fun family night in.

Watch: The Story Behind the Famous Pickle and Peanut Butter Sandwich

This post was originally published on June 15, 2018.