For many Americans, cakewalks conjure settings of school carnivals, fall festivals, and PTA fundraisers. Cakewalks appear to be a cross between musical chairs and a raffle game to the casual observer, played in a large circle of numbered squares. Suddenly the music starts, and revelers walk around the circular path until the melody stops, and the person standing on the chosen number wins the prize: a cake.

However, the cakewalk arose from a history of bondage, appropriation, and minstrelsy—specifically, a Black lineage of subverting and opposing their physical and cultural oppression. Arising in the slave quarters of antebellum plantations, the cakewalk began as a dance of joy and humor before it was twisted and contorted through the lens of a dominant white culture. As Megan Pugh writes in American Dancing: From the Cakewalk to the Moonwalk, "the cakewalk gets at deeper truths, and deeper patterns, all the way down to the country's great unfinished business of slavery."

The Cakewalk's Origins

It would be easy to assume the cakewalk is a cousin of duck-duck-goose or similar children's party games. However, the dance that appeared on plantation grounds in the mid-nineteenth century looked nothing like it does today. A promenade-type dance performed in hand-me-down finery, the dance was meant to parody the movements of the ballroom dancing favored by white elites of the time.

However, cakewalks incorporated movements from African dances, such as shuffles, high-kicks, and twists, and the dances would be individualized by each performer. As champion cakewalker Proctor Knott explained in 1902, "The dance was a cross between a shamble and a strut." Cakewalk numbers could be performed alone or as a couple, and the dances would often include incredible stunts, such as balancing a jug of water on a single hand while continuing to dance.

Their white masters, without understanding the joke, would join in the festivities, clapping along in time and often taking it upon themselves to award the prizes. According to the ragtime musician Shepard Edmonds, born of formerly enslaved parents, "It's supposed to be that the custom of a prize with the master giving a cake to the couple that did the proudest movement."

While slaveowners missed the covert implications of the cakewalk, the white elite asserted control over the revelry in this way, affirming their place at the top of the social hierarchy in the antebellum South. But as Black dancers continued to revel in these caricatures underneath the noses of their enslavers, they reclaimed what little cultural power they had.

Cakewalks and the Rise of Minstrelsy

Following Emancipation, many Black communities continued the tradition of the cakewalk as a point of joy and subversion. But as African-American political will grew during the Reconstruction era, white elites sought to reclaim their political and cultural power through means both overt and subtle.

As the post-war social order tumbled and contorted, Black Americans did something previously untenable: they moved. As formerly enslaved folks and their children spread from the South throughout the country, the cakewalk moved with them, and as it did it continued to evolve. It is no surprise then that the word cakewalk gained mass popularity during the 1870s, according to the Oxford English Dictionary.

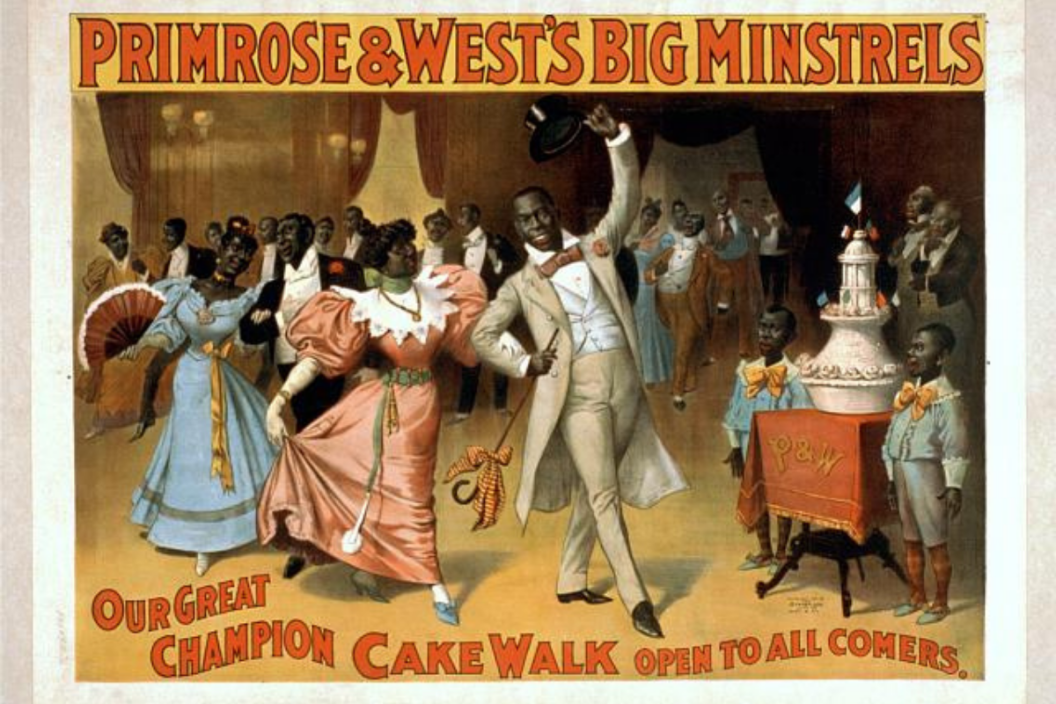

Cakewalks became so popular to both Black and white Americans that they became a regular part of the then-wildly popular minstrel shows, a type of variety show typically performed in blackface. Here, white performers would become the cakewalkers, dancing in outrageously gaudy clothes and with exaggerated movements. These shows, like other forms of minstrelsy, were meant to reinforce the inferiority of Black Americans, turning a joyful dance into a grotesque and infantilizing exhibition.

By the 1890s, cakewalks had become a nationwide fad. The dance became so popular that cakewalk contests began to spring up, culminating in the first annual national championship in 1892, known as the Cakewalk Jubilee. This event, held at Madison Square Garden, showcased fifty couples competing for prizes up to $250.

But as American reached the end of the century, the white social order had been reinscribed into American politics. In the 1890s, as lynching and disenfranchisement became oft-leveraged tools of a racist social order, a Black dance became the zenith of white society.

Cakewalk Reclamation

As cakewalk became a nationwide fad that crossed the color line, Black performers attempted to reclaim the dance. As they did, they worked to imitate and ridicule the white minstrels performing in blackface, similar to those before them dancing in slave quarters. This reclamation—of Black dancers appropriated a minstrel dance first appropriated from Black slaves—highlights what cultural critic Amiri Baraka called a "remarkable kind of irony."

https://www.instagram.com/p/BZgyohIAGi9/

But this reclamation was not only through dance. By 1897, five years after the start of the championship, Black contestants unsuccessfully attempted to have police arrest the Jubilee management for racially prejudiced judging. (They were, of course, unsuccessful.) But the forces of white culture could not be stopped, and by the turn of the century, the minstrel cakewalk had spread to European, and specifically, Parisian society.

As overt minstrelsy faded from view and jazz music replaced cakewalks as white America's preferred Black cultural output, the cakewalk was eventually sidelined to the carnival. As the dance morphed from a contentious, culturally charged dance to a children's game, its meaning and history were quickly occluded.

Next time you're at your local fall carnival or a lively holiday party and the music stops, be sure to tell someone that cakewalks aren't just the carnival games you've come to know. Engage with their history, start a conversation, and spread some historic knowledge along the way.

Products featured on Wide Open Eats are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our links, we may earn a commission.