The America, and specifically the Appalachia, of our ancestors becomes fainter each day. There's no doubt that we have lost intimate knowledge of the land as generations passed, and those basic homesteading skills are what enabled the survival of our families in the mountainous East for hundreds of years. My grandfather's family is from Kentucky and I call him Pappaw, but I had no idea that I was really referring to him as one of the best-kept secrets in America. Let me introduce to you the pawpaw fruit, nicknamed the Appalachian Banana.

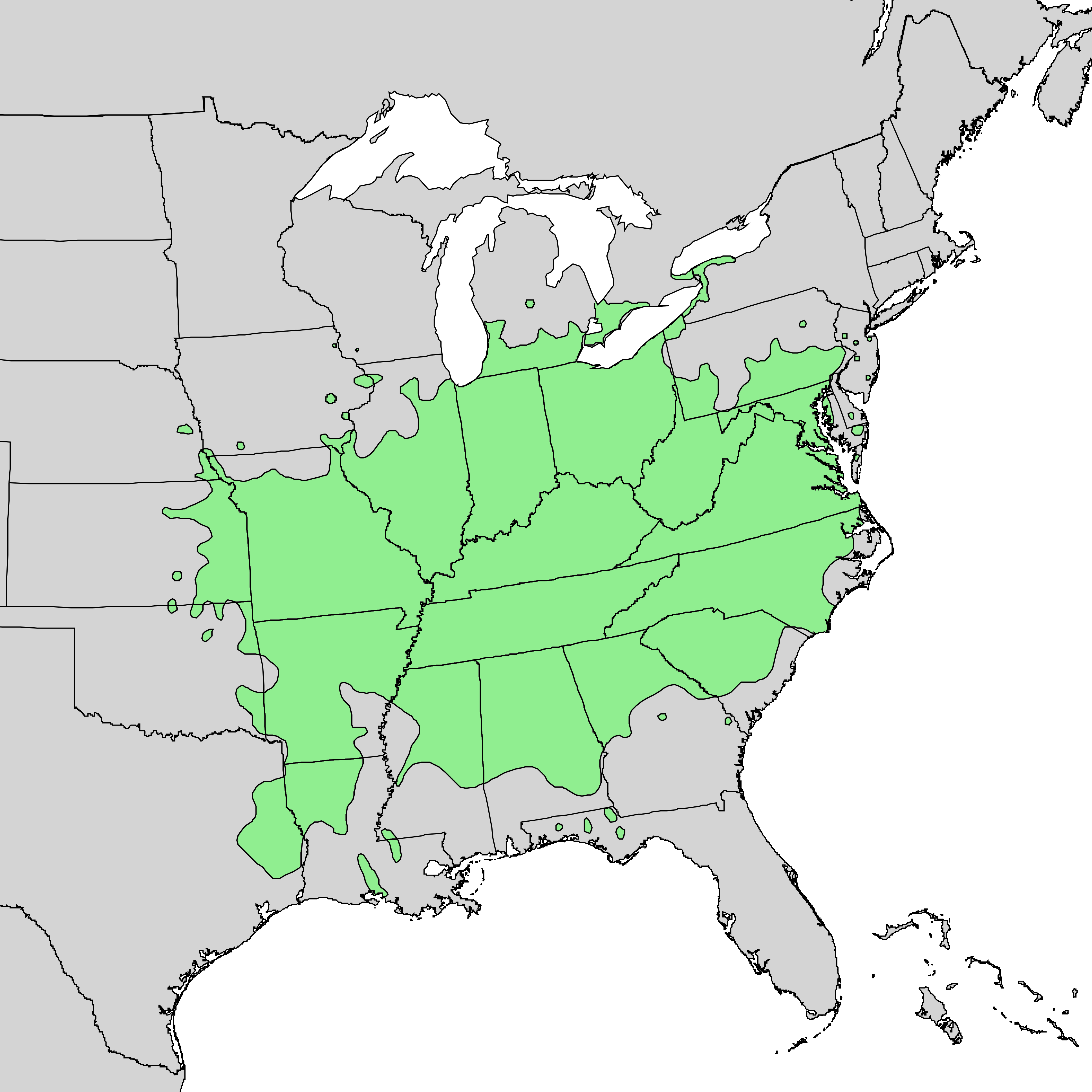

The pawpaw tree, or the Asimina triloba, is a native fruit tree that grows in the Southeast along the Appalachian Range and into regions of eastern Texas and Arkansas. It's a fruit-bearing tree that is found as far west as Nebraska and as far south as Florida, with roots in the east from New York to North Carolina. Many who have tried it say that the custardy flavor of the pawpaw fruit is reminiscent of tropical fruit, like a banana, a mango, and a melon, or like cantaloupe. If you've encountered it before, you might have heard it referred to as the American Custard Apple, the West Virginia Banana, the Indiana Banana, the Quaker Delight, or the Hoosier Banana.

The tropical flavors seem out of place for fruit trees in places like Michigan, West Virginia, and Ohio, but the fact of the matter is that we've simply forgotten about the pawpaw fruit tree and its magical banana-like bearings.

What is the pawpaw fruit?

The University of Georgia lists the pawpaw as a minor fruit of the state, and describes it as "the only cold hardy species of the 'custard apple' family." The trees reach maturity at 15 to 20 feet, and can continue to grow up to 30 to 40 feet. They often form thickets or groves with their ever-expanding root system.

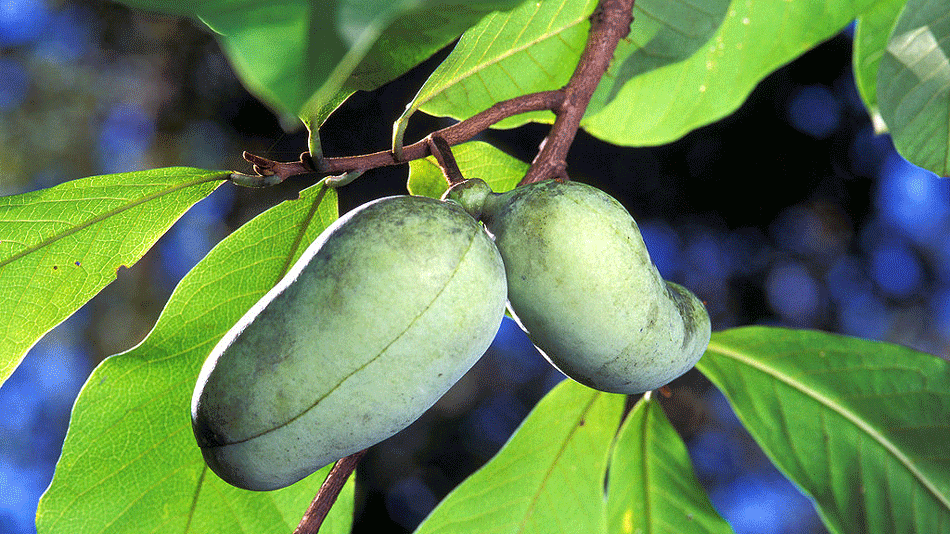

The fruit from the pawpaw is often 2 to 6 inches long and round or oblong, often in a similar shape to a mango. Inside the fruit are creamy centers with non-edible seeds; the flesh of the fruit is too soft to dice. The nutty banana flavor associated with the fruit comes from this sweet custard center, and the sunny electric flavor also offers a yeasty and floral aftertaste, which is why, as Serious Eats reported, there is a small market for pawpaw beer.

The fruits themselves are "rich in minerals, such as magnesium, copper, zinc, iron, and manganese, potassium, and phosphorus," according to Dave Tabler with Appalachian History. You eat the fruit by ripping the skin away, slurping the pulp, and spitting out the pawpaw seeds that are often shaped like lima beans. The easy-to-remove seeds are inedible, so don't forget to spit if you encounter a pawpaw. The creamy custard center is reminiscent of ice cream, especially if you've ever blended frozen bananas in a food processor for 'nice cream'.

The ripe fruit keeps for a week in the refrigerator, but you can also make a pawpaw puree and freeze it. The frozen fruit puree is perfect for smoothies or pawpaw ice cream.

A look at pawpaw trees in American history

Pawpaw fruits are the largest edible fruit indigenous to the United States, and the first earliest documented mention of pawpaws are in a 1541 report of the Spanish-led Hernando de Soto expedition of North America. This expedition focused on modern-day Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, and Arkansas, common regions for the pawpaw fruit. In the snippet, he referred to the Native American cultivation of the fruit east of the Mississippi River.

In the Appalachian Mountains, George Washington loved chilled pawpaws for their sweet custard flavor as his favorite dessert, and NPR confirmed that Thomas Jefferson planted a grove of pawpaw trees on his Monticello estate. Further, the news organization even found that once, he had pawpaw seeds shipped to France in 1786.

Members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition lived by the pawpaw on their travels, and the fruit was so prominent in the country that there are towns named after the pawpaw in a few states, like Oklahoma, Kentucky, Michigan, and West Virginia.

For settlers in the woods of Appalachia and the Midwest, pawpaws were often the only fresh fruit around. So what happened to America's love of the pawpaw? As it turns out, a dedicated group has remained loyal to the forgotten fruit tree for generations.

What happened to the pawpaw fruit?

The pawpaw is now considered one the pure American fruits that foragers love to seek out on the East Coast. Many kayakers as far as east as western Maryland to Arkansas often head out on the river in search of pawpaw trees and fresh fruit to eat immediately on their journey. Pawpaws were never commercialized in the country because these fruits bruise easily and have a short shelf life when ripe.

As soon as they ripen and fall from the tree, they begin to ferment and their fresh flavor will only last one or two short days at room temperature at home. Refrigerated, they'll keep up to a week, though they're known to be finicky little things. They don't freeze well because their centers are so soft, and they don't ship well because they are so soften. When it comes to ugly produce, a pawpaw would rot on a grocery store shelf before someone would be brave enough to try the bruised fruit.

It's hard to grow because the tree's flowers are reported to smell like rotting meat, and the pawpaw seed is said to be poisonous. This fact alone puts off even the most adventurous home gardeners.

How can I find pawpaws?

The easiest way to locate pawpaws is to forage for them if you live in the region. To access pawpaws today, you might get lucky when a farmer's market sells them or you can choose to grow your own pawpaw patch. There are also several pawpaw festivals around the country, including ones in Maryland, North Carolina, West Virginia, Ohio and Pennsylvania.

Pawpaw season usually lasts for a month and runs from late August through October, depending on location. Pawpaw trees tend to grow along creek banks or river bottoms, and because they are smaller trees, they usually grow as an understory tree. You can spot a pawpaw tree from its maroon flowers.

As Sara Bir, the author of The Pocket Pawpaw Cookbook and contributor for Serious Eats, wrote, "Pawpaws at the peak of ripeness simply fall from the tree, whereupon they get smashed and icky. So the key is to pick almost-ripe pawpaws, the ones whose stems break off with no resistance from the branch." That direction for foraging reveals a lot about the pawpaw, in particular its evasiveness to our industrialized food production industry.

Mentions of the fruit disappeared in historical texts around World War I, and it wasn't rediscovered until the mid-1970s, as the Christian Science Monitor reported, when a geneticist named Neal Peterson simply picked one off the ground and bit into it. Kentucky State University and Kirk Pomper are leading a decades-long pawpaw research program to develop the trees as a long-term alternative to tobacco production in the state, one of its most lucrative crops even today.

However, all hope is not lost for the pawpaw. There is a small resurgence movement enlightening Americans to the largest edible fruit in the United States, and we can only hope it continues because it's up to us to preserve this long-lost fruit, one we tossed out when it no longer met our industrialized and commercial needs.

This article was originally published on February 19, 2019.