If you've eaten an oyster on the half-shell from Florida's Gulf Coast, chances are it was an Apalachicola Bay oyster.

Until the last decade, more than 90 percent of Florida oysters came from Apalachicola Bay, the tributary where the Apalachicola River enters the Gulf of Mexico. But because of a toxic mixture of overharvesting and ecological disaster the oyster population has plummeted in recent years, prompting the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission to shut down all oyster harvesting two years ago. They will remain closed until at least 2025.

A Fisherman tongs oysters from the cat point oyster reef in Apalachicola Bay. (Photo by Mark Wallheiser for The Washington Post via Getty Images)

The implications of this decision continued to be discussed, with vocal advocates on both sides of the issue. While some harvesters are pushing to get back on the water as quickly as possible—often to support themselves and their families in the industry they grew up in—others are reticent to return, hopeful that oyster populations will rebound for younger generations.

Florida's Oyster Industry

The oyster industry has long dominated this small Southern locale. Native populations inhabited the regions for thousands of years prior to Spanish arrival in the 1700s; the shell mounds surrounding the area are a testament to indigenous reliance on the abundance of bivalves. Although the city was officially incorporated under the name "West Point" in 1827, it was renamed Apalachicola only four years later, an indigenous word understood to mean "land of the friendly people."

Although the first iterations of the colonist community predicated the town's industry on cotton and lumber, by the civil war, the local industry had begun to rely on the mollusks. Oysters were sold locally by new settlers as early as 1836, and, according to Eater, barrels were being shipped into the northern colonies by 1850. By this time, Apalachicola was the third-largest port on the Gulf of Mexico, behind only New Orleans and nearby Mobile, Alabama. "By 1896, Apalachicola was exporting 50,000 cans of oysters per day, led by the Ruge Brothers Canning company and Bay City Packing Company," Eater explained.

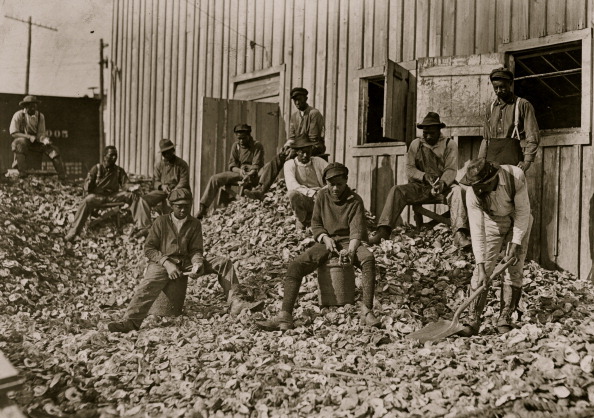

Oyster shuckers at Apalachicola, Florida, 1909 (Photo by Lewis Wickes Hine/Buyenlarge/Getty Images)

Modern Apalachicola—population 2,354—has continued to rely on oyster populations just as the forebearers of the land did. Prized for their salty-sweet taste and large, plump bodies, tourists have long flocked to the town, known fondly as "Apalach."

The Apalachicola fishery has been in operation since the mid-nineteenth century. As such, for generations, local families have made their living and life's work harvesting wild oysters. Local fisherman Shannon Hartsfield, a fourth-generation seafood worker, told NPR, "On both sides of my family, our livelihood has always been on this water."

Apalachicola Bay Oysters and the Environment

Although the oyster fishery shut down briefly in 1985 and 1986 following the damaging effects of Hurricane Elena, it has been running more-or-less consistently for more than 150 years; short closures were always followed by an immediate rebounding of the local oyster populations. However, in recent years, the problems facing the waters have continued to grow, with oysters suffering the most drastic consequences.

James Creamer, right, and Victor Causey tong oysters from the cat point oyster reef in Apalachicola Bay. (Photo by Mark Wallheiser for The Washington Post via Getty Images)

For more than 30 years, Georgia, Alabama, and Florida have been engaged in a battle known as the Tri-State Water Wars over control of the shared Chattahoochee River water flow. (Alabama and Florida have long contended that Georgia uses more than their share of this freshwater supply, diverting necessary water into metro Atlanta. Although the supreme court ruled in favor of Georgia in early 2021, these battles continue to rage.) Oyster reefs thrive on a delicate balance of fresh and saltwater systems; as sources of freshwater dry up, the rising salinity levels damage the reefs.

The 2011 BP oil spill along the Gulf Coast significantly toxified the waters, and in 2012, the reefs almost collapsed entirely due to severe drought. (Legacy fisherman Hartsfield hasn't harvested any oysters since 2012 due to these conditions.) Although the numbers of oysters along this Florida Panhandle town have been declining for three decades, it was only around this time people began to understand the gravity of the situation facing their waters. By 2015, these mounting problems began to gain national attention.

The oystermen and women who have made their lives on with tongs on these oyster reefs are struggling with both the impact of the decline in oyster populations, as well as their inability to perform their livelihoods. But the local collapse of this industry has far-reaching implications beyond the fisheries.

"Oysters are indicator species, keystone species," Riverkeeper Georgia Ackerman told NPR in 2020, immediately following the harvest ban. "They tell us a lot about the overall health of an estuary and ours has been in trouble for a while."

Getty Images

The stationary bivalves filter and clean the water they reside in, while also providing crucial habitat to hundreds of other species vital to the bay's ecosystem. (Similar to coral reefs in tropical waters, oyster reefs are excellent indicators of the overall health of the water system they reside in.) The mollusk's reliance on both fresh and saltwater places them directly outside of coastlines, where they perform similar functions to barrier islands. Oyster reefs serve as barriers to tides, absorb the brunt of ravaging storms, and often prevent erosion while protecting productive estuary waters.

The problems facing Apalachicola Bay are not radically different from the problems facing oyster populations around the world. According to a recent study, 85 percent of oyster beds and reef habitats have been lost globally, while many bays have seen a 99 percent reduction of oysters. Similar to Florida, these reefs are facing problems from over-harvesting and polluted waters.

But as the study's authors explained, the greatest problem of all currently facing oyster populations is an intellectual one: "Many obstacles hinder successful management of oyster reefs; one of the most pervasive is simply the perception among managers and stakeholders that no major problems exist."

Through ongoing education and direct intervention in affected waters, you may live to eat another Apalachicola oyster in your lifetime.

READ MORE: Oyster Crabs: The Teeny, Tiny Seafood Delicacies You're Not Eating